By Derryl Murphy & William Shunn

Lungs burning, Luke Bryant risked a quick look back over his shoulder as he sprinted through the gray afternoon. The Dixon twins were still keeping up. Henry, in fact, was even gaining ground. Luke tried to run faster, but his feet felt like bricks. He couldn’t keep going much farther. Him and his big mouth! When was he ever going to learn?

The main road here ran east to west along the southern edge of the woods. The Dixons had been lying in wait as he walked home from school, anxious to deal with Luke and his big mouth. When they popped out of hiding with their pimply faces and their scraggly whiskers in need of plucking, Luke had shoved Henry to the ground, told him to do something unrepeatable to his grandmother, and taken off running.

Somewhere along the way he had lost his textbooks, probably at the scene of the ambush. His uncle was going to kill him.

He heard a motor behind him in the road. Freddy the Finn, owner of the men’s clothiers in town, tooled past in his new Essex, waving jauntily and honking his horn. Yeah, thanks, Luke thought.

The graveyard, son, came his father’s voice in the back of his mind. It’s your only chance.

Luke shook his head. His parents were three years gone, but still he sometimes imagined he heard them in place of the conscience that was getting more and more of a workout these days. The graveyard was just ahead, on the north side of the road, and beside it the little Methodist church that mostly farmers like his aunt and uncle attended. But he couldn’t hide in the graveyard, not with the statues waiting there to watch him . . .

He heard the Dixon boys yelling from around the bend, getting closer, and that decided him. Graveyard it was. But not by the front entrance.

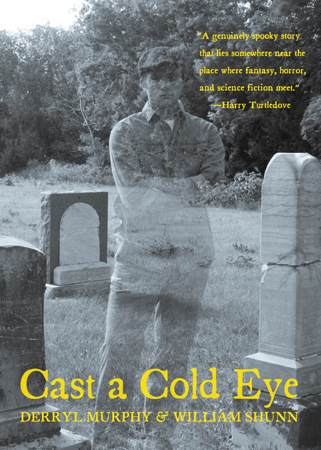

The wrought-iron gate flashed past on his right, flanked by decorative free-standing brick walls choked with ivy. Just ahead, a strange pickup truck was parked in the dirt lot beside the little church. Under the rust and dirt it showed a faded rainbow of colors. An enclosure of weathered gray plywood spanned the bed, peaked like a small house. Several holes had been patched over with old canvas, and painted on the side in cramped black letters was:

Annabelle Tupper

Spirit Photographer

Reasonable Rates

It was an odd thing to see at the church, but perfectly placed to cut behind for cover as he plunged into the woods west of the graveyard.

With what felt like a spear impaling his side, he snaked his way through the leaves and lashing branches, heedless of the cuts and scrapes he was no doubt collecting on his hands and face. He thought he could hear Henry and Clay yelling back in the road, but that only spurred him on. He hardly spared a thought for the statues.

When he stumbled into a clearing, he immediately turned and crouched, listening intently for any sounds of pursuit. There were none, only the sound of the melancholy breeze in the trees, the desultory chatter of birds, and the heaving of his own ragged breath as he gasped for air. Dappled shadows fluttered around him like the watery light in a dread enchanted kingdom at the bottom of the sea. He looked up. Above the old elms with their leaves just turning brown, the sky was a drab slab of gunmetal. It didn’t look cloudy, but still the heavens were dull and gray. He shivered. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d felt the sun on his skin, or even felt warm.

Was that why he kept doing things like slurring Henry Dixon’s grandmother, especially when he knew how close the boy was to her? So stupid. He hadn’t always been so damn dumb. He used to get along with everybody.

When was the last time he’d seen the sun blazing in all its glory in the vault of the sky?

It must have been, must have—

A gradual prickling of the skin at the back of his neck forced him to remember where he was. He slowly turned from the screen of trees to face into the small clearing. It was less a clearing, really, than one of several little side niches that had been carved from the trees that surrounded the cemetery as the Spanish flu had snatched more and more people from their sickbeds and deposited them here unceremoniously. That had run its course three years since, but the town of Branchville still staggered under the weight of the decimation. But that wasn’t what gave him the whim-whams so bad here.

In the clearing, no more than ten feet away, stood a little stone cherub atop a fancy grave marker maybe three feet high. The cherub was contorted like cherubs always seemed to be, like the ecstasy of the Lord’s glory was too much for their stubby bodies to bear, but its eyes weren’t fixed blindly on high. No, its eyes were somehow open, in a deeper sense than the always-open dead stone should have been, and they were looking at him, watching him, boring straight to the center of his head.

Luke bit back a whimper. The eyes, the stone eyes, were so full of agony and yearning, as if the statue were struggling to free itself from its prison of stone and pull Luke’s soul into some ghastly embrace. This was why he avoided the graveyard at all cost, though cutting around it meant an extra twenty minutes on the walk home from school. The statues didn’t always open their eyes to look at him, but it was often enough that every time he’d vow never to set foot on this haunted ground again. But he was so stupid, he wouldn’t ever learn.

The statue hungered for him, he could sense it. Ice clogged his heart and his hands shook. A beating from the Dixons was surely no worse than this. Preferable, even. Stupid!

The air was dry with rot and leaf dust. Luke’s feet itched, and the side of his face tingled as if swarming with ants. He turned his head to the side, looking out the little cut in the trees at the rolling gloom of the graveyard’s main field. He could see at least six other statues looking at him from out there. Three were angels of varying sizes, two more were somber-looking little men carved into big monuments, and one an equally glum-looking woman.

He dropped his gaze, not willing to meet the statues’ eyes for one moment more, but even as he did he knew he shouldn’t. He realized where he was, and what he would see beneath him.

Two gravestones, simple and unadorned.

He hadn’t visited this leafy alcove since that terrible day three summers ago when the papers certifying the end of his world had been stamped and finalized. He barely remembered it, barely remembered there being other markers, let alone a cherub on a pedestal. Now, as then, he only had eyes for the two gravestones that bore the inscriptions:

Seamus Bryant

Husband and Father

1878-1918

Colleen Bryant

Wife and Mother

1887-1918

The spans of the dates were too brief to be believed.

A spray of red wildflowers rested against each stone. They dissolved into garish, profane streaks as tears blurred Luke’s vision. The red was the brightest color he remembered seeing in ages, bright and vivid as arterial blood.

He stood paralyzed for several moments, paralyzed in shock and grief. It only sank in slowly how close he was to the two gravestones, maybe as the mournful barks and howls of a distant dog broke through his hypnosis. When he realized he must be standing directly atop his mother’s grave, an electric shock seemed to galvanize his legs, as if anticipating the touch of bony fingers through the soil. He was running before he knew it, weaving between half-seen markers, monuments, and headstones to the main gate, pressed on by the terrible reminder of his parents’ absence, and by the many eyes that awakened, opened, and followed his frantic passage.

He thanked God that at least his parents’ gravestones were plain, and devoid of any carven faces.

The cemetery occupied a swath of the shrinking woods that slithered east and west like a river of green and faded yellow and brown, dividing Branchville and the rocky southern hills from the rich flat farmlands to the north. Before he reached the gate, he came back to his senses somewhat and plunged back into the trees, curving toward the church.

Panting, he hid at the verge of the dusty, tire-flattened lot beside the church and surveyed the scene. The truck he’d seen earlier was gone now, but Pastor Wegkamp was there, standing with his back to the trees and staring down the road west. The Dixon twins were nowhere in sight. Luke emerged from the trees and stood stooped over, hands on knees, sucking in great breaths. The pastor turned at the sound.

“Ah, speak of the devil and he appears,” said Wegkamp, his horsey face splitting in a grin filled with large, somewhat mismatched teeth. He crossed the distance between himself and Luke and assumed the same hands-on-knees position. The pastor was so tall that his face was still several inches higher than Luke’s. “Are you all right, son? Are you the reason those twins were making such a ruckus out here?”

Luke nodded wordlessly, and the pastor’s brow creased in worry.

“Son, you look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

A thousand words clotted Luke’s throat, crushing each other in their rush to get out, with the result that none did. Tears of rage boiled behind his eyes. He squeezed them shut and lowered his head.

Wegkamp patted Luke’s shoulder with an awkward, oversized hand. “I know, Luke, I know,” he said. And of course, the pastor did know, having lost his wife and child to the flu. “It does get better, though.”

Gasping, Luke managed to force one word out: “When?”

The pastor let out a heavy sigh. “When you learn to let go and . . . and just keep walking. It’s not easy. The Lord can help.”

Wegkamp said no more, and the two of them stood in the parking field for all the world like two football players talking strategy. But Luke still couldn’t get all the jagged words out from inside himself. A swarm of flies seemed to buzz in his head. He pounded a fist on the meat of his thigh. He wanted to tell the pastor about the statues and their prying, hungry eyes, but here in the open it didn’t seem to have the force of truth—a sailing ship that had lost its wind.

“Luke, your aunt and uncle love you,” said the pastor, and now Luke could look up again, Wegkamp’s words having lost their force of truth. The pastor’s face was almost pleading beneath his unruly shock of red hair. “You go on home to them. There might be . . . be something interesting waiting there. Go on.”

The pastor patted Luke again on the shoulder and straightened up. Luke didn’t want to go home, but he had to in any event. There were chores to see to, and Uncle Roy wasn’t one for letting them slide. Still, Luke felt angry and dismissed, like he was being sent away before he’d got the chance to say his piece. What would he say, though, even if he could?

Luke nodded slowly and turned to walk west on down the road.

“Beautiful day, though,” said the pastor behind him.

When Luke looked back over his shoulder, Wegkamp was shading his eyes as if from a fierce glare as he gazed down the road. Luke couldn’t see why, and it gave him a chill. “Sure,” he said, but it was one of those words that come automatically and don’t mean anything.

Luke hiked himself down the road’s verge, under the gloom of the flat gray sky. It was a long walk home, but at least it was time alone, not having to deal with other people and their concerns, their demands.

After ten minutes he turned north up the Old Flats Road, a double-rutted track that meandered through the woods, winding like it had been cleared by a drunk. He skirted the ditch at the side of the road, with no more than a trickle seeping along its mulchy bottom. The leaves beginning to change should have made the narrow lane a lovely sight, but to Luke it was all dull—as uninteresting and dull as the weathered gray side of a barn.

He turned east again on the far side of the woods, only to be startled by the barking and snapping of a startled hound a few yards away in the road. “Aw, Chuck,” said Luke, shaking his head as he brought up short. “You crazy mutt.”

The big bluetick hound backed away as quick as it could, still barking, while Luke watched. Chuck belonged to Cal Hunter a couple of spreads over, and it and Luke used to be good friends. Something had happened, though. Maybe all the people dying had made it a little crazy. If so, Chuck wasn’t the only one.

The old dog wasn’t dangerous, but it sure seemed ambivalent now about Luke. When it had enough distance, it started padding back and forth in a nervous line, staying at least twenty feet from him. It whined as if it wanted to come closer, but Luke knew from experience that if he took a step toward it Chuck would only growl and maybe start barking again.

“Aw, get on with you,” Luke said, waving a dismissive hand at the dog. He kept walking, and Chuck backed further into the road, whining, as Luke passed it. And now it would no doubt follow him, keeping a respectful distance, of course, all the way to his uncle’s place.

That’s just what happened too. Ten minutes later Luke turned down the track at the start of his uncle’s property, and when he looked back he saw Chuck park himself in the fallow field where now only wildflowers grew. The dog began to whine. Luke took a step back in Chuck’s direction, but the dog sprang up and bared its teeth. He put his hands up.

“All right, boy, all right, I’m going,” Luke said.

As he set off up the track, the dog barked once and ran off.

The house was still a good walk ahead, nestled up against a stand of tall trees, with a battered but roomy old shed a ways off across a dirt sideyard. And parked between, besides Uncle Roy’s van, was the spirit lady’s rainbow-hued truck.

What was that doing here? His uncle was a hard, pragmatic farmer, and didn’t hold with any of that spiritualist stuff. The thought of anyone trying to convince Uncle Roy about ghosts and such made Luke chuckle and wince at the same time. Chince? Wuckle? Or was this the surprise Pastor Wegkamp had hinted at?

Luke groaned. “That’s all I need,” he muttered.

His boots were good and dusty by the time he made it to the side of the house. The barn and stubbled fields beyond looked gray and somehow unreal. But he smelled woodsmoke, and the fine aroma of baking pie. As he mounted the steps to the enclosed side porch, he heard voices from the kitchen. He stepped lightly, eased open the screen door to the porch, had a seat on the bench inside to pry off his boots. He could smell something else hot and savory on the stove, but his stomach wasn’t interested.

“It’s like the boy walks around under a cloud,” he heard Uncle Roy say from inside.

“It’s the loss, of course,” said Aunt Maura. “He’s sensitive, that one.”

“Lazy, more like. Moping, distracted. Can’t count on him for a lick of work.”

A new voice cut in, a woman’s, but low. “Preacher said maybe something new for him to try might help. Something interesting and involved. I’d certainly pay you for his time.”

“Be more’n I get out of him now, that’s a cert,” Uncle Roy said.

Luke stood up and banged the porch door a little, on purpose. The voices quieted down. Luke rattled around on the porch a minute, then opened the door to the kitchen and the extra smell of fresh coffee. Three faces turned toward him, Aunt Maura by the stove looking pretty and tired in her clean but cluttered domain, Uncle Roy seated at the table with his hands clasped on its surface, and across from him the apparent owner of the truck, her face turned only half toward him.

Luke gasped a little, his breath catching. At first he thought a skull had turned its hollow-eyed gaze upon him.

“You’re late, boy,” Uncle Roy said. “Now say hello to our guest.”

“You must be Luke,” said the stranger, turning in her chair and offering him a hand. “Annabelle Tupper. Pleased to make your acquaintance, kid.”

“Miss Tupper,” he said, stepping forward to take the woman’s hand, and using the opportunity to study her face. What he had taken for a bony socket was really her right eye, entirely black where it should have been white. A few splotches of black stained her right cheek. Her other eye, which he hadn’t seen at first, was normal, with an iris of striking gray. She wore an open oilskin duster, faded dungarees tucked into shiny leather boots, and a heavy blue wool sweater. Her hair was long and brown, shot through with streaks of gray, and bound with a leather cord. She gripped a battered, shapeless suede hat in one hand.

“Oh, please, son,” she said, “it’s Missus, but if we’re going to work together you’ll have to call me Annabelle.” She smiled as she said it, and the deep laugh lines at the corners of her eyes deepened.

“I’m . . . sorry?” said Luke, taking a step back and glancing toward his uncle and aunt.

Uncle Roy frowned and rubbed the shiny top of his head. He was a gangly man with a homely face, browned by the sun, his fleshy lips usually pursed in disapproval, like now. “Mrs. Tupper makes photographs, and she needs an assistant while she’s in town. She’s made us a very generous offer for your time. I think we’d be fools to refuse.”

“But—” But that’s spirit photography, Luke wanted to say. His heart seemed to tremble inside him.

Uncle Roy forestalled him with a raised hand. “Your chores, yes. With what Mrs. Tupper’s offering, I can bring on a man to help out for a few days.”

“I do look forward to working with you, kid,” Mrs. Tupper said. Her smile looked friendly enough on its own terms, but the blackened eyeball gave everything she said a tinge of menace. “I asked your pastor there at the church if there were any hard-working young men around I might take on, and he sang your praises long and loud. The Lord himself must get gray hairs listening to that man go on!”

That didn’t sound much like Pastor Wegkamp to Luke. He looked at Aunt Maura, but she wasn’t meeting his eye.

“It’s settled then,” said Uncle Roy with a nod. “You’ll help Mrs. Tupper get her equipment and such settled out in the shed. Then you’ll get cleaned up. The way I hear it, you and her’ll be making a call or two this evening.”

“Yes, sir,” Luke said with a deep sense of resignation, and dread. Really, there was nothing else to say.

Mrs. Tupper drained the enameled metal coffee cup in front of her and stood. She was tall, taller even than Luke by a good couple of inches, though part of that might have been her boots. “No reason not to get started,” she said. “I’ll get the truck pulled around and opened up.”

Luke belatedly reached for the kitchen door to open it for her, but Mrs. Tupper’s hand was already on the knob. She smiled as if to say Thanks anyway, and her squinting black eye seemed to grin at him as well. Luke followed her out onto the porch and sat down in one of the cane chairs to pull his boots back on. As Mrs. Tupper pushed through the screen door and descended to the sideyard, Uncle Roy joined Luke on the porch.

“Where are your books?” Uncle Roy asked. “I’ll run them up to your room for you.”

Luke’s stomach clenched, but he didn’t look up from tying his laces. “They’re . . . I left them at school.” He hadn’t given them another thought since losing them in the confrontation with the Dixons. He’d have to find them in the morning on the way to school.

Uncle Roy released a sigh like the air hissing from a punctured tire. “What are you going to be without books, boy? Lord knows you’re no great shakes as a farmhand. I hardly know what to do with you, most times. If you weren’t Maura’s sister’s boy, I’d a had to turn you loose way back.”

Luke finished tying his shoes and sat with his head down, his ears burning. Uncle Roy pulled the door shut behind him and came around in front of Luke.

“Look at me, boy.”

Luke wasn’t sure which was harder, looking at a stone cherub staring back at him with haunted eyes, or looking up into the craggy, disapproving face of his uncle. But right then he figured he would have taken the statue.

“This arrangement with Mrs. Tupper ain’t just for my benefit, though I’m sure whatever hungry man I hire’ll give me three times more work than ever I get out of you. No, I’m trying to do right by your mother and maybe point you into an honest trade that suits your temperament, since you seem so determined to treat school same as you do farm work. You got a good head on your shoulders when you care to use it. You pay attention to that lady and work hard for her, maybe you’ll just pick up a skill you can make a living off. You understand me?”

Luke’s eyes stung. It would almost have been easier to take if there were any rancor in Uncle Roy’s tone, but Luke knew it was a fair assessment. It made him angry at himself and embarrassed to hear it all laid out like so flat like that, and he wanted to do good, to do better. But still. But still . . .

“But making photographs of spirits?” Luke protested. It came out sounding petulant, like a child, and Luke’s ears burned.

But instead of getting angry, Uncle Roy squatted down so he was looking Luke near level in the eye. From the yard came the sound of the truck starting up. “Well, I grant there may be an element of charlatanism to what the lady does. But that doesn’t mean there’s not honest techniques to be learned from her, and Pastor Wegkamp did send her our way.”

Luke wanted to protest that it wasn’t the prospect of charlatanism that worried him, it was the prospect that what Mrs. Tupper did was real. Instead he nodded meekly in the face of his uncle’s iron pragmatism.

Uncle Roy narrowed his eyes. “So you’re ready to work hard and learn?”

“Yes, sir,” said Luke.

“Good boy,” said Uncle Roy, unsmiling, and clapped Luke on the shoulder.

Mrs. Tupper had backed her rainbow-hued truck up to near the door of the shed by the time Luke joined her. The enclosure built up on the bed had a small door with a latch secured by a padlock. She unlocked it with a key she got from a leather cord around her neck and opened the door to reveal crates, trunks, and tanks packed in as neat and tight as the pieces of a puzzle.

“My little rolling kingdom, snug as a turtle’s shell,” Mrs. Tupper said with a grand gesture. She might have been a magician on stage, presenting the climax of a cunning illusion. “The ones marked ‘Darkroom’ will go in the shed, kid. My valise too.”

The daylight was dying, a dull glow to the west, as Luke opened the door to the shed. Mrs. Tupper ducked through behind him. At some point since leaving the house she had covered her head with her shapeless brown hat. “Home, sweet home,” she said, looking around.

“You’re actually going to stay in here?” Luke asked, incredulous. The plank walls were fairly tight, no chinks of the dying day showing through, but even by the light from the open door the place looked anything but welcoming to Luke. The left half was cluttered with garden tools, random engine parts, two spoked wooden wheels, an overturned wheelbarrow, and a plow as tall as a man. Shelves and a pegboard lined the walls just inside the door, home to hand tools, seed packets, slightly damp catalogs, and an old trunk with some of Luke’s parents’ things in it. The right half of the space was more open, with a moldering bale of hay and a low daybed pushed into the far corner at right angles. A battered bridle hung from a nail near the cot. Indistinct shapes lurked above between the rafters and the roof.

Mrs. Tupper stood in the middle of the space and turned in a slow circle. “Oh, long as I can bundle up nice and lay my head someplace halfway soft, there ain’t much in the way of humbleness I find I mind.” She pursed her lips and pointed to the worktable in the darkest corner of the shed. “I think we’ll set up the developing trays and such over there. We’ll have black paper for the door and windows, and maybe on top of that we can rig up my black drapes from the rafters around that space. We can run an electric connection in here from the truck if there’s not one already.”

What a lot of work this was going to be! Luke felt weary and blue already, just thinking about it. But as the two of them hauled boxes inside from the truck, Luke’s curiosity got the better of his resentment and dread.

“How’d you get that eye, ma’am?” he asked with a nod toward her face. “If you don’t mind my asking. Was it from a ghost?”

Mrs. Tupper looked startled for a moment, then began to laugh, a low, easy, companionable sound. She set down the crate she had carried in. “First off, I told you once already, I need you to call me Annabelle. Not ma’am, not missus, not Ol’ Mother One-Eye. All right?”

“Sure,” said Luke. “Long as you call me Luke, not kid.”

Mrs. Tupper let off a loud guffaw. “Guess I can’t argue with that, young Master Luke. And secondly, no, this eye of mine weren’t from no ghost.” Her voice grew sober. “It was from years in the darkroom, Luke, accomplished with some of the very chemicals you’re carrying in that there crate. So please be gentle with them. The mixtures we used to use to tease a picture out of exposed plates can be very dangerous. Less so now with dry plates than back when this happened, but still it’s well to give this stuff plenty of respect. You only get back as much respect as you offer, that’s what Carl always used to say.”

She had turned her head partially away as she spoke, and in the gloom her bad eye looked like a hole bored straight through her head and out the other side. Luke set his crate down very gingerly with the others. “Carl, ma’am?” he asked, then added, “Er, Annabelle?”

She snorted a little and sat down on a stack of two crates. “That would be Mr. Carlton Jarvis Tupper, who bequeathed me his name and all this pelf you see piled around me, may God rest his damned peripatetic soul.”

Luke wasn’t sure what she meant by that, but he did know enough to feel awkward and abashed. He stood there twisting his hands together. “I’m sorry to hear that, ma’am.” She fixed him a look with her good eye. “Annabelle, I mean. Was it, you know, the flu?”

Mrs. Tupper shook her head slowly. “No, Luke. It was . . . it was an accident, before the flu and before the war.”

“It was the flu took my ma and pa,” said Luke, and the words surprised him. He hadn’t meant to say that, hadn’t meant to say it by a stretch, but they came from a bleak and scoured place inside him he hardly even knew was there.

Mrs. Tupper—Annabelle—nodded. “I guess we all have a score to settle on that account.” Something in her voice gave Luke a little chill. “And that’s good. It’s what keeps us up and drawing breath. Now let’s get these crates on opened up.”

With everything set up in the shed, Luke and Annabelle set out for their first appointment of the evening, Luke behind the wheel of the old truck. “I’m glad you can drive,” Annabelle said. “I’m blind in this eye, and so most days when I’m on the road I get a headache something fierce.”

Luke glanced over. “Does that happen to a lot of photographers?”

She laughed hard. “Now, what good would a world full of half-blind photographers do, Luke? Most of ’em are more careful than I was, and anyway, like I said, we don’t use wet plates much anymore.”

“Wet plates, ma’am?”

“It’s an older way of taking photographs. Even the dry plates I use now’ll soon be set aside for sheet film, next time I get to a city with a decent photography shop. Wet plates still have their uses, though, particularly if you need to shoot and develop right there in the field.”

Luke looked over at Mrs. Tupper, frowning. “Why would I want to develop a photograph in a field?”

Annabelle guffawed. “In the field, meaning anywhere away from your darkroom. Kid, I can see you have a lot to learn. This might even be fun.”

In town, she directed Luke to an address she had written down, which turned out to belong to Fredrik Virta and his family. Luke cast his eyes appreciatively over the big house. “I didn’t realize we were coming to see Freddy the Finn,” said Luke. The gleaming black Essex was parked in an open garage to one side, like a show object.

“Freddy the Finn?” said Annabelle with a disbelieving expression.

“Well, he’s not really Finnish,” said Luke, “but his father was, so that’s what everybody calls him.”

“Ah. Well, why don’t you start unloading the boxes and that canvas bag I showed you while I go check in.”

Luke had dressed up in the best non-Sunday clothes he had, and waxed his hair down too, so he moved stiffly as he carried boxes into the Virtas’ immaculate drawing room.

Freddy himself, portly and blond, was standing there to greet Luke. Along with his wife and their seven frighteningly well-behaved children. Annabelle had explained already that she was training an assistant, and everyone in the room seemed keen to watch him and her assemble the equipment.

First she reached for the canvas bag on Luke’s shoulder. She untied the drawstring and reached inside. “This is a tripod,” she said, pulling out a three-legged wooden stand. “Put it up for me, and then we’ll set up the camera.”

Luke had seen some cameras around town before, but they were always little things—Brownie boxes, or else flat devices that unfolded with a small leather bellows. Annabelle’s camera was a large but slim box, wood and brass and glass on one side; on the opposite side was a small screwhole. She showed him how to thread that onto the tripod, then helped him open up the camera once it was safely in place. It turned out that this camera had a leather bellows as well, patched in several places, but it was much bigger than anything he’d seen in Branchville. He watched carefully as she put the rest of it together.

“This camera makes eight-by-ten-inch negatives, which gives great detail for the kind of work I do.” She took a large black cloth from her case and attached it to the back of the camera, over the glass. She herded the Virtas into place before the mantelpiece, crouched, tucked her head beneath the cloth, and fiddled with the camera and tripod. After a minute or so she stood back and gestured for Luke to have a look.

Afraid of what he might see, Luke nonetheless ducked his head under the cloth. For the first few seconds he just stared at the glass, confused, not really sure what he was seeing. It was the Virta family, but not as he had just seen them in the flesh.

“Everything’s upside-down!” he exclaimed.

“Sure is,” said Annabelle, sounding amused. He tilted his head to try to compensate for the change in perspective. “Keep your head up, Luke. You’ll just get a crick if you try and turn yourself over. It takes a bit of getting used to, but eventually you’ll be able to take in everything this way. A world that’s rightside-up won’t ever look the same.”

Annabelle took his hand and brought it up to the side of the camera, resting his fingers on a rough-edged metal wheel. “Turn this slowly,” she said. “One direction and then back the other way.”

Luke did, and watched as the family’s faces fell out of focus. He turned it the other way and watched them come back into focus.

Now Annabelle showed Luke how to close the shutter on the lens and how to place a plate holder into the back of the camera, over the glass. “Now this is a light-tight box,” she said. “It’s waiting for us to expose the plate we have in there, but before that we have one more thing to do.”

She taught him quickly how to read the light to make a proper exposure, and then told him how to open the shutter. “When you squeeze the bulb, hold it tight for four steamboats. Everyone”—this to the Virtas—“please hold very still, and look straight into the lens.”

Luke took a deep breath and squeezed the rubber bulb. He counted slowly to four, and released it again.

“Very nice,” said Annabelle. “Now everyone stay where you are. I’m going to do one more just in case.”

And to Luke she said quietly, “Good work, kid. You learn fast. You might just work out after all.”

With the equipment all loaded up and the plates carefully stowed, Annabelle said to Luke, “Do you know the way to an Edna Martens’ house?”

In his pocket, Luke was rubbing the edge of the shiny new dime Freddy had slipped into his hand a few minutes earlier. “The Widow Martens?” Luke said, amazed.

“Do you people here have a folksy name for everyone roundabouts?” Annabelle asked dryly.

“Everyone that deserves one, I guess. But yes, I know where it is. Everyone in town knows where it is. How’d you get an appointment there?”

“Forethought and research,” she said, locking up the back of the truck and heading for the passenger door. “I try to know my town before I ever set foot in it.”

Luke, going around the other side of the truck, paused before opening the door. He peered across the hood at Annabelle. The last purple shreds of sunset clung to the sky in the west. “You didn’t know about me before you got to Branchville, did you?”

She laughed, a booming sound in the night. “Not on your life, kid. You’re what we in the trade call a happy accident.”

“Which trade would that be?” Luke said, opening his door. “Photography, or humbug?”

He climbed in, and so did Annabelle, and he could sense her giving him a sidelong look in the dark. “A little of both, if you must know, Luke. But probably less humbug than you might think, all right?”

Luke started the truck and put it in gear. That wasn’t what he wanted to hear. He wanted reassurance that what Annabelle did had no commerce whatsoever with any invisible realm. “Yes, ma’am,” he said, somewhat shortly.

“Something on your mind?” Annabelle asked mildly as the truck rumbled off to the south.

Luke blew out a breath, not knowing what to say. “I just . . . well, darn it, you didn’t even say a word about spirits or the like there at the Virta place.”

“Should I have?”

“I thought that’s what you do.”

Annabelle chuckled. “Did you see any spirits at that house, Luke?”

His breath caught in his throat. “Well . . . no.”

“There you go. Me neither. I’m a photographer, kid. I can’t very well shoot a photograph of what ain’t there, now, can I?”

Anything but reassured, Luke kept his mouth shut after that and drove.